What ‘Me Too’ reporting and OnlyFans have in common

From ‘trauma-dumping’ to online abuse, there are more similarities than you’d think.

Before we jump into things… Let’s do just a tiny bit of house-keeping. First of all, a massive thank you to everyone who has subscribed to my newsletter. I set out to do this spontaneously and had zero expectations for circulation. I just hoped it would provide a friendly outlet for me to share my thoughts outside of 280 characters.

700 subscribers and a mention in Vox (thank you, Rebecca!) later, I am incredibly grateful that people care about what I have to say. Even when people vehemently disagree.

This blog has also been a welcome respite from my day job, but if you’re looking for my reporting on these topics, check out my articles at Insider and subscribe to read my investigations. My last big one was a deep dive into labor disputes at James Charles’ Sister Sister LLC, plus allegations he uses the “N-word” slur privately. Insider’s digital culture team has you covered 7 days a week (but not me right now ‘cause I’m on vacaaaation).

Also, I would love to commission an artistic reader to do a little graphic design for the blog. I’m looking for a logo and cover photo that scream GEN Z HELL. Send me your portfolio & rates to kathryntenbarge @ gmail dot com. You can know my full name. We’re friends here.

And without further ado…

Conversations with friends

One of my best friends since childhood has her own OnlyFans. She’s not famous and you’ve never heard of her, but she makes well above minimum wage selling amateur porn online to an audience of thousands of people. She’s like a porn micro-influencer.

Her job is extremely tough. If you think being a pornstar is hard, try doing porn without being a star. There’s a huge stigma around it, so she doesn’t want her content to get leaked and her identity to become known. This is a problem, because people leak her and other sex workers’ content constantly on sites like ThotHub.

OnlyFans is also a really hard platform for its performers to use, since there’s no reliable creator support unless you’re a celebrity. Regular ole’ OnlyFans creators can DM the Twitter support account (which isn’t even verified, by the way) and they might get an unhelpful non-response back, according to my friend.

For example, my friend says she’s reached out to OnlyFans multiple times about her content getting leaked, which the platform vaguely promises it will resolve with copyright strikes. She says they’ve never done anything to help her, although they’ve scoured the web to help out big names like Belle Delphine and Tana Mongeau.

[Edit: It’s noteworthy to include that Belle also participated in a scheme while underage to lift other SWers content and sell it as her own. I interviewed her about the controversy here.]

Beyond the technical difficulties she experiences, my friend also struggles with her customers. The men who seek out her services ask her to make incredibly violent, dehumanizing content. They ask her to do things that are just plain gross or painful. They’re mean and abusive in private messages.

Nonetheless, my friend keeps at it, because she’s drawn to sex work for a lot of the same reasons OnlyFans has exploded during the pandemic. It’s reliable, good money. She can do it from home. And once you’ve started, it’s hard to convince yourself to stop.

We have a lot of conversations about our jobs, like friends do. And during one recent chat, I was venting about my own experiences with “Me Too” reporting and how my life has changed since writing exposés about famous YouTubers.

My friend pointed out that, while there are obvious and plentiful differences between what we each do, there are some surprising similarities. It got me thinking about sexual trauma, online work, and how women online are used as punching bags.

Trauma-dumping and the pressure of 24/7 availability

Our conversation kicked off when I brought up how much I sometimes wish people would just stop talking to me. I’ve been “Extremely Online” as far back as I can remember, spending more time on the internet than off.

But becoming a reporter who covers the internet and the people who get famous on it has totally transformed my online life. For one thing, I have an audience, which is stressful. But also, because of what I cover, I have people reaching out. Constantly.

This is a necessity of the job. Because I cover — well, allow me to gesture broadly at my phone — everything, I can’t always just go to real places and talk to people in real life. I need them to come to me, in my direct messages and emails and texts.

Not only that, but ever since I wrote the Vlog Squad exposé about Durte Dom and David Dobrik, I have become somewhat of a go-to for people who have complaints about influencers, ranging from severe allegations against creators to petty gripes from fans.

Don’t get me wrong, I welcome tips, and I don’t want to discourage anyone from reaching out with a story. It’s just a steep mountain to climb at all hours of the day, and not everything people send me is helpful.

My inboxes are at least three-quarters full with spam, hate, random questions, random comments, and actual messages from people I know in real life who are trying to reach me. It’s enough to make me want to fling my phone across the room at any given moment.

I’ve stopped using some apps entirely (or at least dread going on them) because I know I’ll get guilty and anxious seeing all the unread messages or conversations I started and no longer have the time or energy to continue.

As it turns out, my friend with an OnlyFans feels the same way. She has thousands of customers, after all, and many of those people pay more to have conversations with her. She also has to cross-promote content on her Twitter account to get followers who turn into paying subscribers.

And the nature of conversations we both have with people we meet online often revolve around sexual trauma. In my case, I interview a lot of people about the sexual trauma they’ve experienced in graphic detail. In my friend’s case, she not only gets people asking her to re-enact fantasies about sexual trauma, but she also gets people “trauma-dumping” on her.

There’s not much when you Google “trauma-dumping,” but there is an opinion column written by a California State student. Korin Chao defines “trauma-dumping” as “how people will abruptly overshare their traumatic experiences in a manner that may feel toxic and self-victimizing.”

Chao compares “trauma-dumping” to cyberbullying in that people feel more comfortable doing it under the guise of either online anonymity or just because they can hide behind a screen rather than have a face-to-face conversation. Chao points to TikTok comment sections as a place where people tend to compete for who has the worst trauma.

I wouldn’t call my interviews with sexual assault accusers “trauma-dumping,” since I’m willingly soliciting details from them. I do get a lot of DMs with people looking to trauma-dump. I’ve had to start drawing lines in the sand when I’m working on specific articles rather than searching for tips, because people dump so much trauma on me that’s unrelated to anything I’m working on.

At the same time, I don’t blame people for trauma-dumping — oftentimes there’s nowhere else for them to go, and I try to be at least a listening ear to people whenever I can. The resulting conversations can often be productive, stimulating, and sometimes even result in great stories. But there’s a dark side to it, too.

It’s fascinating to me that my friend’s customers also “trauma-dump” on her. They’re taking advantage of the position she’s in, where oftentimes she’s receiving money to have conversations with them. But while she’s prepared to sext, she ends up shouldering someone else’s traumatic life story.

I’m sure I don’t even need to say it, but this isn’t great for anyone’s mental health. Both my friend and I have talked about how our jobs can exacerbate our mental health conditions, and anyone coming from a place of unresolved “trauma-dumping” needs therapy, not a stranger on the internet. Unfortunately, therapy and mental health care is still widely inaccessible to people who need it.

Becoming a faceless punching bag

One not-so-surprising phenomenon on the internet is the sheer amount of harassment and negativity that women encounter. Sex-based online abuse is something that we’ve accepted and normalized to the point where we deny it’s even happening.

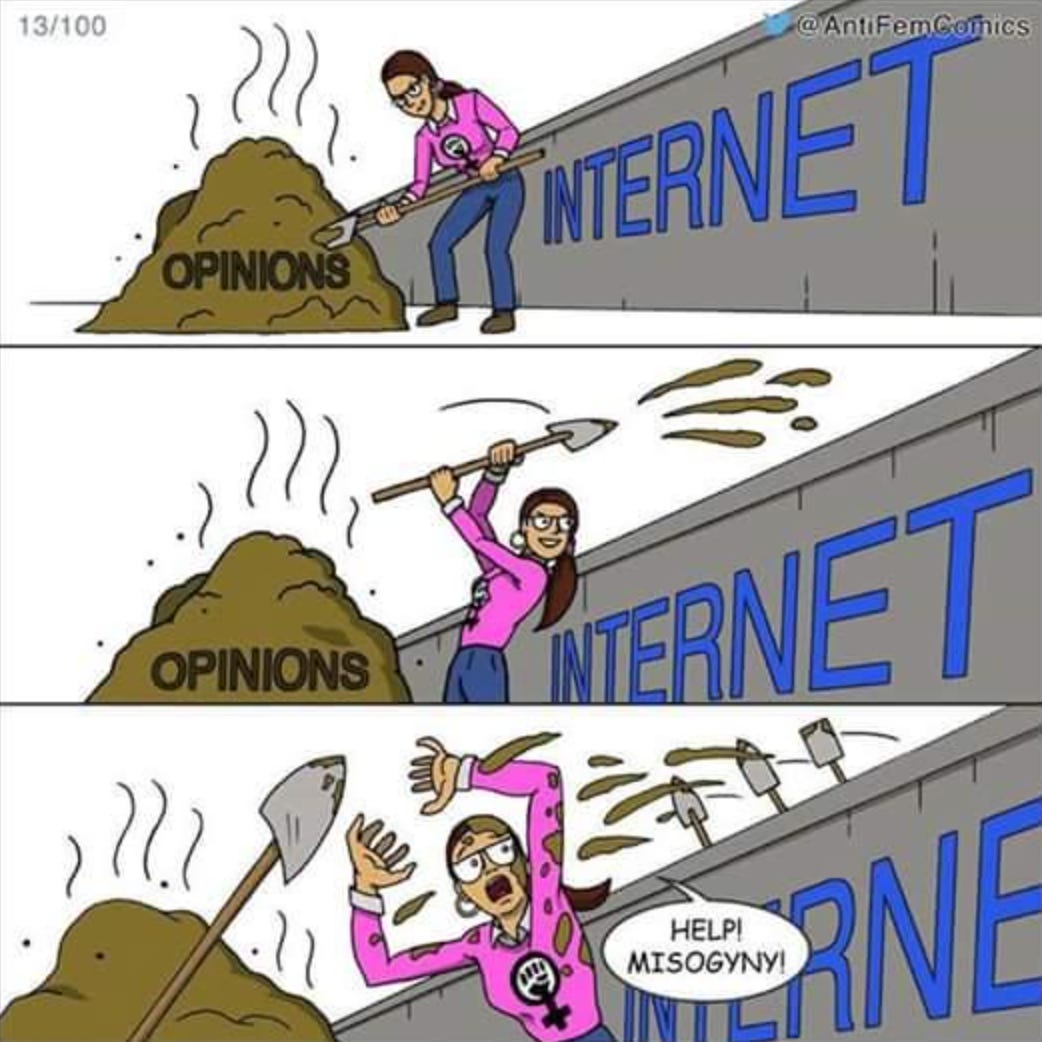

People like to tell me and other women that we “can’t take criticism” or that we’ve earned it. There’s one meme in particular that shows a woman shoveling bad opinions over a wall and being surprised when shit comes flying back.

But that’s not usually what we’re talking about. I know personally I’ve accepted a ton of good faith criticism over the course of my two years in professional media, from how I act on Twitter to how I carry myself in on-air interviews. I’ve sought and digested criticism about my work internally at Insider and externally when I face my critics online.

It’s not good faith criticism when someone DMs you to tell you that they’re flying out to you tomorrow to kill you because of what you did to David Dobrik. It’s not good faith criticism when someone makes a 15-minute YouTube video about one of your tweets that ends with them telling you that you’ll rot in hell.

It’s not good faith criticism when someone writes a nasty tweet at you demanding to know why you didn’t include a piece of information in your article when you did and they just didn’t read it. It’s not good faith criticism when it hinges on your appearance, on you being a girl, on you being a certain age, or on whether you have a blue check.

It’s not good faith criticism when someone belittles your entire profession and all of your work based on their hatred of “the media,” a hatred that tends to fall apart considering there isn’t a person alive who doesn’t seek out news.

My friend doesn’t get any good faith criticism whatsoever. She doesn’t get people politely suggesting how she could improve her branding. She gets some of the worst verbal abuse — period. Not just on the internet, just period.

People ruthlessly attack my friend for being a slut and a whore and the fault of all of society’s ills because she dares to profit off her own sexuality. Oh, the horror! A woman getting naked for money! This will surely be the end of us.

Of course, it’s often the same people who watch porn. They just don’t like the idea of sex workers taking their power back through platforms like OnlyFans. They don’t like the idea of having to pay for porn. Some of the things people say to my friend make my stomach hurt, others make me laugh because they remind me of what people say about Insider’s paywall.

“We both make stuff that people regularly and willingly consume and demand, but then they still feel the need to take out all their anger and insecurities on us for it,” my friend said.

So what are the roles of journalists and sex workers?

I struggle with talking about the bad side of my job because at the end of the day, I love what I do. I am incredibly blessed to be in a position to do something that I’m passionate about for a living. And I certainly don’t want to come off sounding bitter toward my own sources, who are people I sometimes genuinely bond with, in multiple ways, through trauma.

I also don’t have a clear, concise answer as to what my own role is in the media ecosystem that engulfs digital news and platforms like YouTube. My beat isn’t new, and neither is the reporting, but I do feel like I’m in a somewhat unique position as a self-proclaimed “influencer watchdog.”

So while I’m still figuring out what my role IS, I can tell you some of what it ISN’T. I’m not a therapist or a victims’ advocate, as much as I appreciate both of those fields. I’m not an expert at helping people unpack their own trauma, although I like to think I ask good questions.

Multiple survivors have told me that they’ve found some kind of closure through just the reporting process, pre-publication. I think there’s something uniquely affirming about going through it, from both sides. You have someone taking your trauma seriously. And I do my best to support my sources in coming forward, from respecting their boundaries to walking them through what to expect when going public.

Despite the potential closure from a story getting published, or even going viral, I’m not a one-woman accountability process. I can't singlehandedly make people face consequences, and I think some of my online critics get frustrated that I can’t and take their overall dissatisfaction with injustice out on me.

Both I and the people I write about — men and women and non-binary individuals — go through hell online for accusing powerful people of things like sexual assault. If my sources are anonymous or otherwise lack an online presence, I still see people trying to pick apart their stories in my replies and DMs and comment sections.

Some of the abuse aimed at my female sources in particular reminds me of what vitriol my friend with the OnlyFans greets online every day. There’s a lot of slut-shaming targeted at women who accuse men of raping them. As far as feminism has progressed, sex is still viewed as something women must have, but privately and to pleasure a man.

When a woman decides to upend that sexual narrative and sell her own body, some people get really pissed. When a woman points her finger at a popular man and says he violated her, other people go to great lengths to deny the violation occurred.

But a journalist doesn’t exist to defend someone’s honor. A journalist exists to expose the truth. A sex worker doesn’t exist to uphold the social constructs around sexual purity. A sex worker exists to provide a service to those who want it.

The major similarity between my experience as a journalist and my friend’s as a sex worker is that we are both women whose roles exist online, exposing us to people who need us and people who mistreat us. We try to fulfill our functions on platforms that aren’t built for us or for women in general. Our work reflects a society that has yet to fully recognize women as equal counterparts to men, or that people are deserving of empathy more than profit.

We shoulder the burden and carry on, because what other choice do we have?